Taos is a remarkable example of a traditional type of architectural ensemble from the pre-Hispanic period of the Americas and unique to this region which has successfully retained most of its traditional forms to the present day. Thanks to the determination of the latter-day Native American community, it appears to be successfully resisting the pressures of modern society.

The culture of the Pueblo Indians extended through a wide geographical area of northern Mexico and the south-western United States. Taos is the best preserved of the pueblos north of the borders defined by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848). Located in the valley of a small tributary of the Rio Grande, Taos comprises a group of habitations and ceremonial centres (six kivas have been conserved), which are representative of a culture largely derived from the traditions of the prehistoric Anasazi Indian tribes who settled near the present borders of Arizona, New Mexico, Utah and Colorado.

Taos's modest rural community appeared before 1400, characterized by common social and religious structures and traditional agricultural practices. In the modern historical period the two major characteristics of the Pueblo civilization were mutually contradictory: unchanging traditions deeply rooted in the culture and an ever-constant ability to absorb other cultures. Their faculty for acculturation gradually began to appear following the first Spanish expedition of the Governor of New Galicia, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, in 1540-42.

The entire 18th century was a time of wars in which Taos played an important part in resisting the colonizers. The breeds of cattle and types of grain were introduced by the conquerors into their agricultural system. Attempts to convert the Pueblos to Christianity were ill-received but unconsciously the religious mentality of the people changed.

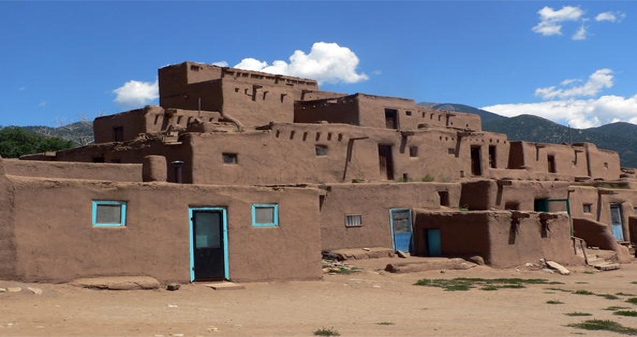

Taos Pueblo shows the traditional method of adobe construction: the pueblo consists of two clusters of houses, each built from sun-dried mud brick, with walls ranging from 70 cm thick at the bottom to about 35 cm at the top. Each year the walls are still refinished with a new coat of adobe plaster as part of a village ceremony. The rooms are stepped back so that the roofs of the lower units form terraces for those above. The units at ground level and some of those above are entered by doors that originally were quite small and low; access to the upper units is by ladders through holes in the roof. The living quarters are on the top and outside, while the rooms deep within the structure were used grain storage. The roofs are made from cedar logs, their ends protruding through the walls; on the logs are mats of branches on which are laid grasses covered with a thick layer of mud and a finishing coat of adobe plaster. It is a massive system of construction but one well suited to the rigours of the climate.

In 1970 the people of Taos obtained the restitution of lands usurped by the government, which included the sacred site of the Blue Lake. At the same time, their ritual ceremonies include both a Christmas procession and the Hispano-Mexican dance of the Matatchines.

The two main adobe building complexes retain their traditional three-dimensional layout. Certain features, such as doors and windows, have been introduced over the last century. Taos Pueblo represents a natural evolutionary process: it has adjusted to a changed social and economic climate and reflects the acculturation of European traits and the relaxing of needs of defensive structures.

Administration of Taos Pueblo is vested in the Taos tribe, which is deeply conscious of its heritage and of the material expression of that heritage in the buildings of the settlement. The pueblo of Taos has tended to become a seasonal habitat reserved for ceremonial functions and tourist attractions.

Historical Description

The culture of the Pueblo Indians extended through a wide geographical area of northern Mexico and the southwest United States. It can still be found in a certain number of communities in the States of Chihuahua (Mexico) and Arizona and New Mexico (United States). Taos is the best preserved of the pueblos north of the borders defined by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848). Located in the valley of a small tributary of the Rio Grande, Taos comprises a group of habitations and ceremonial centres (6 kivas have been conserved). which are representative of a culture largely derived from the traditions of the prehistoric Anasazi Indian tribes, who settled around the present borders of Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado. Their culture went into an irreversible decline, and in the later 13th century major sites like Mesa Verde and Chaco (included on the World Heritage List in 1978 and 1987 respectively) were abandoned, perhaps because of major climatic changes.

The proliferation of small pueblos in the valley of the Rio Grande and its tributaries, when considered along with the disappearance of the Anasazi tribes, was one of the major characteristics of the settlement of the North American continent. Modest rural communities. characterized by common social and religious structures, traditional agricultural practices perfected during the "classical" period. and a systematic use of irrigation, were built. Taos is thought to have appeared before 1400.

In the modern historical period the two major characteristics of the Pueblo civilization were mutually contradictory : unchanging traditions deeply rooted in the culture and an ever-constant ability to absorb other cultures. Their faculty for acculturation gradually began to appear following the first Spanish expedition of the Governor of New Galicia, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado. in 1540-1542. Beginning in 1613, the inhabitants of Taos resisted the system of encomiendas which allowed certain Spaniards to exact a tribute in kind from the village. In 1634 the missionary Fray Alonso de Benavides complained to the Pope of their "rebellious" attitude.

The entire 18th century was a time of wars in which Taos played an important part in resisting the colonizers. However, the breeds of cattle and types of grain introduced by the conquerors were readily adopted into their agricultural system. Attempts to convert the Pueblos to Christianity were ill-received (during the major Pueblo revolt of 1680 the first church was burned down) but unconsciously the religious mentality of the people changed. A similar dichotomy between an irredentist attitude in principle and an assimilation in fact marked the two subsequent historical stages : from 1821 to 1848, under Mexican administration, and from 1848 to the present, under the US administration. In 1970 the people of Taos obtained the restitution of lands usurped by the Government, which included the sacred site of the Blue Lake. At the same time, their ritual ceremonies include both a Christmas procession and the Hispano-Mexican dance of the Matatchines.

Today, the village appears at first sight to conform with the description given in 1776 by Fray Francisco Atanasio Dominguez. However, although the earthen enclosure which he likened to one of the Biblical cities survives, numerous modifications can be observed.

To the west, the missionaries' convent and church lie in ruins. A new church was built at a different location of the west side of the north plaza in the 19th century. The multi-tiered adobe dwellings still retain their original form and outline, but details have changed. Doors, which traditionally were mostly used to interconnect rooms, are now common as exterior access to the ground floors and to the roof tops on upper stories. Windows, which traditionally were small and incorporated into walls very sparingly, are now common features. The proliferation of doors and windows through time at Taos reflects the acculturation of European traits and the relaxing of needs for defensive structures. In addition to ovens located outdoors, fireplaces have been built inside the living quarters.